|

Monks Kirby is a large village in Warwickshire some 6 miles North West of Rugby.

The Priory Church of St. Ediths, Monks Kirby

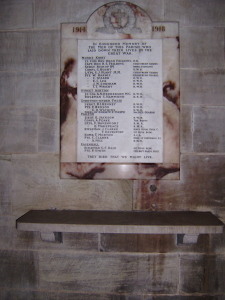

The War Memorial

The War Memorial takes the form of a Stone Cross in Brockhurst Road, Monks Kirby recording those who laid down their lives in the Great War 1914 – 1918 and the Second World War 1939 - 1945 with a Plaque in St. Edyth's Church.

Marble Plaque in the Church

Those who laid down their lives in the Great War 1914 - 1919 and recorded on the War Memorial in Monks Kirby

Grave of Private Fergus Benson

Fergus John Benson Private No. 3123 1st/7th Battalion Royal Warwickshire Regiment (Territorial Force). Killed in action 27th November 1916 and buried in Warlencourt British Cemetery Pas de Calais, 3 miles SW of Bapaume on the Albert – Bapaume road. Records 2,765 UK., 461 Aust., 126 SA., 79 NZ., 4 Can., and 2 French burials and 71 special memorials.

Son of Mr W H Benson of 13 Charles Street, Wolverhampton formerly of Stretton Wharf, Stretton under Fosse, enlisted at Coventry joining the Royal Warwickshire Regiment in 1914. He had been expected home for Christmas. His Platoon Officer wrote “He met his death instantaneously by explosion of a shell a splendid soldier a cheerful little hero who they highly esteemed and in whom they had great confidence.”

1st/7th Battalion was a Territorial Battalion formed at Coventry on the 4th August 1914 and with the 1st/5th, 1st/6th and 1/8th formed the Warwickshire Brigade part of the South Midland Division. The Brigade entrained for Southampton crossing the Channel and landing at Le Havre on the 23rd March 1915. On the 12th April 1915 the Brigade had taken over a sector of the front south of Ypres on the north-east side of Ploegsteert village.

On the 13th May 1915 the formation became the 143rd Brigade of the 48th (South Midland) Division.

Private Benson himself landed in France on the 25th June 1915 as part of a draft of replacements.

In June 1915 General Joffre was proposing two offensives against the German forces; from Champagne northwards and from the Artois plateau eastwards. The offensive from Artois – as planned at the beginning of June – was to be the main operation and formed a sequel to the expected capture of Vimy ridge with a greatly re-enforced French 10th Army attacking eastwards from about Arras and Lens into and across the Douai plain. The offensive from Champagne was to be delivered from about Reims northwards along the foothill of the Ardennes following the eastern border of the plain.

On the 4th June General Joffre sent a draft of his scheme to British G.H.Q. with the British being asked to assist in two ways; by taking over 22 miles of the French line south of Arras from Chaulnes (33 miles south of Arras) across the Somme to Hebuterne (13 miles S.S.W. of Arras) in order to free for the offensive in Champagne the French Second Army the holding that sector of the line and also participating in the French 10th Army offensive by attacking either on its immediate left, north of Lens, or on its right across the Somme uplands south of Arras.

In principle Sir John French agreed to these proposals and the newly formed Third Army was to become responsible for the extended front, in fact of 13 miles rather than 22 miles, from Curlu on the Somme River to Hebuterne,

The first units into the trenches were on the 20th July 1915 1/5th Gloucesters, 1/8th Worcesters and 1/4th Oxford and Bucks. from the 48th (South Midland) Division to hold the area Fonquevillers to north of Serre. On the 24th July 1915 1st Kings Own (Royal Lancasters) and 2nd Essex from the 4th Division, Serre to Beaumont-Hamel. On the 30th July 1915 1/6th Seaforth Highlanders and 1/8th Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders from 51st (Highland) Division, Thiepval to La Boisselle. On the 2nd August 1915 1st Norfolks and 1st Bedfords from 5th Division, Becourt to the Somme River.

Shortly after his joining the Battalion, the Brigade moved south to Lozinghem about 4 miles west of Bethune and then in July 1915 the Brigade moved further south to relieve the French 42nd Brigade in trenches north and east of Hebuterne, Somme, one of the most peaceful sectors of the British line. In September 1915 the Brigade moved further north to take over a sector of the front near Fonquevillers north of Hebuterne from the 111th Brigade of the French 56th Division. Christmas 1915 was celebrated in the line with the observation that strict orders have been given against any fraternizing with the enemy. Private Benson was sent a Xmas parcel and wrote home to acknowledge receipt stating; “I think we are getting on fine now and the war will not last much longer. The Germans don’t retaliate as they did a few months ago. We are turning the tables on them.”

The Somme Offensive was the main Allied attack on the Western Front in 1916. Planned in late 1915 as a joint Franco-British operation it was concerned with territorial gain but also aimed at the destruction of German manpower reserves. French troops were expected to bear the main burden of the operation but the German Army’s assault on Verdun in 1916 turned the Somme operation into a large-scale British attack. After a preliminary bombardment which was expected to completely destroy German forward defences the plan called on the first day for the penetration of the German front line from Serre in the north to Maricourt in the south. In the second phase it was planned to take the high ground between Bapaume and Guinchy, followed by a breakthrough towards Arras and a general advance in the direction of Cambrai. Instead on the 1st July 1916 the attacking troops were cut down with insignificant gains by the French and the British right wing units near Montauban being off-set by total failure to the north. The attacks nonetheless continued in a series of limited and costly advances until in mid July the German second line was finally broken around Bazentin Ridge. On the 20th July a new offensive was launched by the Australians on the ridge at Pozieres and the French well to the south in the region of Foucaucourt but the front remained substantially unaltered throughout August. In September a renewed British attack the Battle of Flers-Courcelette was launched using tanks for the first time but only a small gain was achieved. Renewed attacks in September, the Battles of Morval and Thiepval, continued in October with a pattern of limited Allied advances whenever the weather allowed. British offensives beyond the Flers-Courcelette line, the Battles of Transloy Ridges and the Ancre Heights, were matched by French attacks in the south and the BEF made one last effort on the far east of the salient from 13 November 1916 the Battle of the Ancre (or Beaumont Hamel) before snow on the 19th November 1916 caused the final suspension of the operation.

On the 3rd November 1916 the 48th (South Midland) Division of which the 143rd Brigade was part transferred to Sir William Pulteney’s III Corps and on the 9th the Brigade moved south taking over a part of the front line at Le Sars, on the Albert-Bapaume road. On the 10th November the Battalion had its first spell in the trenches in the front line just to the East of the village of Le Sars, described as most foul and full of dreadful heaps that had once been a community, with a track through it. The Battalion was in the sector to the right of Le Sars holding the line until relieved by the 1st/8th Royal Warwickshire on the 12th November. The Battalion provided working parties on the 13th, 14th and 15th November before moving into Bivouacs at Bazentin Le Petit Wood providing working parties on building new Battalion Headquarters from the 19th to the 22nd, then on the 23rd November the Battalion relieved the 1/6th Gloucester in trenches in the right sector at Le Sars. Over the next four days the Battalion lost 1officer and 1 other rank killed in action and 1 officer and 4 other ranks wounded. On the 27th November 1916 the Battalion was relieved by the 1/8th Royal Warwickshire Regiment and proceeded into support losing 2 other ranks killed in action, and 5 wounded, all by enemy shell-fire. Private Fergus Benson was one of the two killed in action, the other being Private No 4537 Ernest William Darvill who is buried in Martinpuich British Cemetery Pas de Calais which is about 2 miles West of Le Sars, with Warlencourt British Cemetery being about 1 mile east of the village. The 1/8th had 1 officer wounded in the relief and 1 soldier killed, this being Private 5085 George Frederick Baker (the relief being described as very trying commencing at 5 pm and being completed at 11 pm). Private Baker has no known grave and is commemorated on the Thiepval Memorial.

The appalling conditions under which the Army fought in this period were described by Sir Douglas Haig in a report dated 21st November 1916; “The ground, sodden with rain and broken up everywhere by innumerable shell-holes, can only be described as a morass, almost bottomless in places: between the lines and for many thousands of yards behind them it is almost – and in some localities, quite – impassable. The supply of food and ammunition is carried out with the greatest difficulty and immense labour, and the men are so much worn out by this and by the maintenance and construction of trenches that frequent reliefs – carried out under exhausting conditions – are unavoidable.”

Between the front and the reserve positions on the reverse slopes of the Bazentin ridge – Ginchy, Guillemont, Longueval, the Bazentins, Pozieres – stretched a sea of mud more than two miles in extent, and the valley of the Ancre was a veritable slough of despond. Movement across these wastes was by duckboard tracks which, exposed as they were to hostile shell-fire and the disintegrating action of the mud and rain, could only be maintained and extended by arduous and unending labour. The front line was mud with holes in it. If the holes were roundish they were called posts; if oblong they were called trenches with names such as Gusty Trench and Spectrum Trench. They connected with nothing except more mud. The only certainty was that, beyond a certain unidentifiable point you would be shelled continuously from over the bleak horizon.

Private Benson was awarded the bronze Allied Victory Medal, the silver British War Medal and the bronze 1914 – 1915 Star he entering a theatre of war before 31st December 1915. The qualification for both the Allied Victory Medal and the British War Medal is almost the same and these were awarded to army personnel who entered a theatre of war so an individual who only served on the Home Front was not entitled to either.

Percy Bishop Sergeant No. 70261 Berkshire Yeomanry. Distinguished Conduct Medal. Died of wounds 15th November 1917. Commemorated on Jerusalem Memorial in Jerusalem War Cemetery which records a total of 3366 missing from General Sir Edmund Allenby's victorious campaign against the Turks in the Great War.

Percy Bishop was born 1882 in Monks Kirby the son of Jonathan Bishop of Monks Kirby and brother of Albert Bishop. In 1891 Percy was living with his Aunt and Uncle Joseph Malui in Mill Street Dunchurch. He enlisted at Hungerford when resident in London. In 1901 Alfred Bishop aged 25 and Beatrice Bishop aged 23 were living at 75 Main Street, Monks Kirby. Alfred Bishop (and his brother Frank Bishop) were step-brothers to Percy and Albert.

In December 1917 Percy Bishop’s brother Albert was the Farrier-Sergeant Major of the Warwickshire Yeomanry.

The British Army learnt many lessons from the Boer War with the recognition by the War Office of a requirement for mounted soldiers who could shoot well and fight on foot as well as move quickly over long distances. This was something which the Yeomanry had proved they could do and in the Haldane reforms of 1908 the Yeomanry was incorporated into the Territorial Force and organised into 14 cavalry brigades as the divisional cavalry for 14 infantry divisions, being trained and equipped as mounted infantry rather than as cavalry, with the rifle the main weapon. By that date the Berkshire Yeomanry regiment was formed into four squadrons based “A” at Windsor, “B” at Reading “C” at Newbury and “D” at Wantage with Regimental Headquarters at Yeomanry House Reading. With the Buckinghamshire Yeomanry and the Oxfordshire Yeomanry, they formed the 2nd South Midland Mounted Brigade.

At the outbreak of the War on the 4th August 1914 part of the mobilization plan was a re-organisation into three squadrons, “C” at Newbury being disbanded and its manpower redistributed within the regiment. Like many other Yeomanry regiments the Berkshire Yeomanry at first remained in the United Kingdom on home defence duties. On mobilization the Oxfordshire Yeomanry had joined the British Expeditionary Force in France and Flanders on the 22nd September 1914 as G.H.Q. Troops and their place in the Brigade was taken by the Dorset Yeomanry.

From the outbreak of the War until April 1915 the Brigade was based mainly in the Fakenham area of Norfolk.

On the 5th November 1914 war had been declared between Great Britain and France and Turkey.

The Brigade was sent to Egypt in 1915 Percy Bishop landing with the Berkshire Yeomanry on the 21st April 1915. The Berkshire Yeomanry remained in Egypt until August 1915 when apart from 135 Berkshire Yeomen who had remained behind with the horses in Cairo, most of the Regiment sailed from Alexandria on the 14th August 1915 landing at Suvla on the Gallipoli peninsula on the morning of the 18th August to take part in the general attack against the Turkish troops entrenched on Hill 70 (Scimitar Hill) the Regiment sustaining severe losses, 5 officers and 164 other ranks. The Regiment remained in defence on the Peninsula with the other regiments in the Brigade until the 1st November 1915 plagued by heat, disease, lack of shade and water and suffering under the continuous shell and rifle fire of the Turks.

The declaration of war against Turkey made Britain take stock of her vital interests in the Middle East including not only the oil fields of southern Persia but the Suez Canal and Egypt. Intelligence reports suggested that the canal was vulnerable to attack by the Turkish Army although this could only be launched when sufficient Turkish troops had been concentrated in Ottoman Palestine who would then have to cross the inhospitable Sinai desert with limited water supplies. Although a barrier in itself the size of the canal made it difficult to defend, connecting the Mediterranean and the Red Sea and running for abut 100 miles from Port Said in the North to Suez in the south whilst on its western side was the Sweet Water Canal which supplied fresh water to the whole area including the main canal towns of Port Said, Ismailia and Suez and which was to become the source of a piped water supply to British troops in the advance in 1916 – 1917.

The decision having been made to protect the whole length of the canal, the strategy involved halting any invading force and preventing any move down towards Cairo and keeping the canal open so the main British defences were located on the West bank of the canal, where trenches were dug between a series of fortified posts, and posts and trenches on the East Bank (Sinai desert side) protected by barbed wire, the systems being linked by bridge and ferry. The Turco – Egyptian frontier was some 150 miles East of the Canal running from Aqaba at the head of the Gulf of Aqaba to Rafa on the Mediterranean Sea some 30 miles south east of Gaza. It was also resolved having decided to base the defence of Egypt itself on the east, at the canal, that the Sinai desert could be abandoned to the Turks which happened with the Turkish army advancing into Egyptian territory and occupying Sinai settlements about 30 miles West of the frontier line.

Turkey in the meantime had been making plans for a major invasion of Egypt and by mid January 1915 the force was assembled in the Beersheba area some 50 miles West of the Dead Sea. The Turkish troops reached the canal in the early hours of the 3rd February 1915 but the attack failed and by the 4th February the Turkish forces had withdrawn back towards Beersheba. Although plans were made for a further assault these came to nothing. The British also felt their position exposed and in December 1915 Lieutenant General Sir Henry Horne an Artillery Officer was sent to Egypt to advise on new defensive arrangements in essence to put the canal out of reach of the enemy’s long-range guns. Defensive lines were placed well to the East of the Canal with tracks and railway lines constructed; however with the appointment of General Sir Archibald Murray to command the Egyptian Expeditionary Force a change in the policy was conceived, a staged advance into Sinai.

In January 1916 the Yeomanry was reorganized. The 2nd South Midland Mounted Brigade was renumbered the 6th Mounted Brigade comprising the 1/1st Buckinghamshire Yeomanry, 1/1st Berkshire Yeomanry, 1/1st Dorset Yeomanry, 6th Mounted Brigade Signal Troop and 17th Machine Gun squadron. The Berkshire Battery of the Royal Horse Artillery (a Territorial unit) armed with 4 thirteen pounder guns formed the Brigade Artillery. The Brigade formed part of the Imperial Mounted Division which in June 1917 became the Yeomanry Mounted Division the Artillery being constituted as the 20th Brigade Royal Horse Artillery (Berkshire, Hampshire and Leicestershire Batteries).

In July 1916 the Turkish Army began its second advance into Sinai which ended by the middle of August with their defeat at the Battle of Romani which ended any hope of capturing the Suez Canal. Over the next few months the Egyptian Expeditionary Force advanced steadily eastwards until early in December 1916 the railway being constructed, a necessary part of the advance, had reached nearly to the important strategic position of El Arish which had been occupied by the Turks for much of the war. Units of Mounted Divisions entered the town on the 21st December finding it had been abandoned and this resulted in the Turkish army falling back into Palestine in the face of the steady advance of the Expeditionary Force. Rafa a town actually on the frontier line was strongly defended by no less than three defensive systems but the town was captured by the New Zealand Mounted Brigade in a charge which marked the end of the desert campaign.

There then had to be a pause in the advance of the Expeditionary Force to extend the railway lines and the water supply which were in place by March 1917 when on the 26th March there was the first attempt to capture the heavily defended town of Gaza which failed when misleading information led to the attack being abandoned. The first battle of Gaza coincided with a decision of the Cabinet to review its strategy in the Middle East to authorize an invasion of Ottoman Palestine and the capture of Jerusalem so making the next attack on Gaza a priority but the Turks had begun to construct a very substantial defensive system extending to the west to the Mediterranean and to the east a series of redoubts with additional Turkish Divisions being used to extend the line further east to Beersheba itself. The first moves in the Second Battle of Gaza began on the 17th April and the operation was much like a major attack on the Western Front with artillery bombardments and a disappointing use of tanks. The Berkshire Yeomanry with other elements of the Imperial Mounted Division was ordered to mount a diversionary dismounted attack during the course of which the regiment captured a number of the enemy trenches and fought off further Turkish attacks. In fact, overall the operation was a failure for a number of reasons, being described as a costly total defeat for the British army with a total of 6444 killed, wounded or missing. The opposing troops then dug in with a stalemate situation lasting for months as the British planners tried to find a feasible way round the obstacle.

On the 27th June 1917 General Sir Edmund Allenby arrived in Egypt to take over command of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force from General Murray. His arrival was a strong stimulus to the troops. To study the ground he visited every part of the front, and the vigour of his personality impressed itself on officers and men. The Commander of the Desert column Lieutenant General Sir Philip Chetwode had prepared for General Allenby an elaborate appreciation of the situation upon which General Allenby based his subsequent plan of operations. The obvious line of advance into Palestine for a force with full command of the sea was along the coast. It was the most direct; it secured the advantages of naval co-operation; it covered the main line of communication to Egypt; it presented comparatively little difficulty in the matter of water-supply. But Gaza which barred the coast route, had become a fortress to be taken only by the slow and costly progress of siege. General Allenby described Gaza as a strong modern fortress, heavily entrenched and wired, offering every facility for protracted defence with the remainder of the works down to and covering Beersheba being a series of strong localities. The centre was strong as well, an open plain dominated by a ridge on which the Turkish defensive works were placed and almost devoid of water. There remained the Turkish left. The Turkish main position ended at Hariera some 4 miles west of Beersheba. Whilst the Turkish garrison at Beersheba would have to be reduced and the water-supply of that place secured, it offered an opportunity to work round an open flank through which a great mass of mounted troops might pass to operate against the Turkish rear. In July 1917 Allenby notified London of his requirements for additional resources, mainly artillery and another infantry division, 5 squadrons of aircraft and additional engineer, signal and medical units.

The plan was simple: to concentrate a superior force against the Turkish left (Beersheba) whilst inducing the enemy that the main attack would be directed against Gaza (Turkish right flank). The early capture of Beersheba with its water supply was a keystone of the plan but there was no question that the Turks would become aware of preparations for a move against Beersheba but attempts were made, as it turned out successfully, to persuade the enemy that the move against Beersheba was a feint with the main attack being against Gaza.

The operation was postponed from September until the 27th October 1917 and consisted in a crescendo of blows alternating at either end of the Turkish line, over 20 miles apart, and the engagement should properly be called the Gaza-Beersheba battle rather than the Third Battle of Gaza. First was the heavy bombardment of Gaza by land and sea and then the assault on Beersheba. Four infantry divisions were placed within striking distances of the main defences to the south and west of the town whilst the Desert Mounted Corps was to ride round to the east of Beersheba by a night march of 25 to 30 miles over stony tracks and enter the town from that side where the defences were comparatively slight. On the night of 30 – 31 October some 40,000 troops of all arms were on the move taking up positions for the assault on the Beersheba defences next morning. The main defences some 3 or 4 miles from the town and the wells were captured with small loss by midday on the 31st October and everything then depended on the attack from the East by the Mounted Corps. A Brigade of Australian Light Horse was ordered to advance straight on Beersheba and the Brigadier though the ground was unknown and the enemy resistance unsubdued determined to make the attack mounted. In the last hour of daylight the brigade rode over the Turks who still stood between them and Beersheba and entered the town securing the very important wells. The next object was for the 20th Corps to advance and turn the Turkish flank at Beersheba but that could not happen immediately and so to draw the Turkish attention away from Beersheba, Gaza itself was to be attacked and this was ordered for the night of 1- 2nd November and was made on a front of nearly 3 miles, reaching all objectives and fulfilling its mission of attracting enemy reserves to Gaza although heavy losses were sustained. The final phase of the operation was postponed until the 6th November when three Divisions broke the Turkish left and forced the hurried retreat of their whole line and on the morning of the 7th November it was found that the Turks had abandoned Gaza with the enemy streaming north along the coastal plain in hasty retreat.

On the 3rd November 1917 the Berkshire Yeomanry moved to Imara some 15 miles East of Gaza to Brigade Reserve remaining there until the early hours of the 5th November when the 6th Mounted Brigade marched out for Beersheba. The Regiment arrived south of the town of Beersheba at 1900 on the 5th November remaining there until at 2200 the Regiment saddled up and marched North to Tel Khuweilfe some 10 miles North East of Beersheba remaining in that area until 0400 on the 6th November when the Regiment was ordered into Reserve but could hear heavy firing from the North East. At 0630 on the 6th November the Regiment moved into action in support of infantry and was in action all day advancing some 3 to 4 miles and sustaining losses of 1 officer and 1 other rank wounded before digging in for the night. On the 7th November near Khuweilfe the Regiment was relieved at 0400 by the Australian Light Horse and withdrew to Brigade H.Q. but by 0600 had marched out to the forward Observation Line to hold this line with infantry which was held all day under heavy shelling and rifle fire. At 1600 on the 7th November the Regiment was relieved by the Lincolnshire Yeomanry when the horses were sent into Beersheba for watering.

At 0630 on the 8th November when the horses returned from Beersheba the Regiment marched North rounding up a party of Turkish snipers with intermittent shelling by the enemy all day and then in the evening went back to Tel el Sheria some 12 miles North West of Beersheba to water the horses and bivouac leaving at 0500 on the 9th November heading East to Huj some 8 miles East of Gaza to bivouac that night some 2 miles South of Simsin about 8 miles North East of Gaza. The Regiment left Simsin at 0500 on the 10th November reaching Nejile some 20 Miles East of Gaza at 12 noon and having watered the horses again headed North engaging the Turks about 1600 bivouacing for the night south of the Arak – Jibrin road with the Regiment in Brigade Reserve. On the 11th and 12th November the Regiment was steadily moving North East as the Egyptian Expeditionary Force swung round after the retreating Turkish troops heading generally towards Jerusalem.. By the night of the 12th November the general line of the enemy and the general disposition of his troops were becoming clear to the British command. The Turks were hastily consolidating a line of defence to cover Junction Station some 30 miles North of Gaza and a similar distance West of Jerusalem and in this area the enemy had no great natural strength except for one narrow steep-sided ridge on which stood the village of Maghar some 6 miles from Wadi Sarar or Junction Station. Whilst Junction Station was the immediate goal Sir Edmund Allenby’ eyes were fixed upon another more distant and politically more important goal. With the railway junction taken he would have reached a line on the latitude of Jerusalem and close to two roads from Jaffa to that city of which the southern road was the best in Palestine. The overall plan was for the cavalry to attack Turkish positions to the south of the road from Gaza to Junction Station, the Infantry divisions would advance up the Gaza road towards Junction station whilst the Yeomanry Division were positioned to the left of the infantry. The main obstacle to further progress was the El Maghar ridge. It was decided that the Buckinghamshire and Dorset Yeomanry should attack the ridge with the Berkshire in reserve whilst the infantry attacked the defended villages of Qatra and El Maghar.

Having bivouacked overnight, on the 13th November at 1420 the Brigade moved out to support the infantry attack on El Maghar. The Berkshire Battery R.H.A. unlimbered and came into action against Maghar at a range of 3000 yards. The Buckinghamshire and Dorset Yeomanry emerged from shelter in a Wadi to attack the ridge and had 4000 yards to cover beginning at once to attract Turkish artillery fire. After a mile the two regiments broke into a gallop as plunging Turkish machine-gun fire fell. The Dorsets had the furthest to go and one squadron had to dismount at the foot of the ridge and attacked on foot; the other squadrons and the Buckinghamshire charged on and on reaching the crest of the ridge the Turkish defenders fled. The Berkshire had moved into the Wadi when the other regiments left and were ordered to assist the infantry in the capture of the village of El Maghar. There remains one controversial point. On the Yeomanry side it is stated that the Berkshire Regiment took the village on foot, no infantry being in the village until after it was taken whilst the King’s Own Scottish Borderers declare it was they who captured the village whilst the Yeomanry merely took the prisoners.

The Berkshire sent in over 900 prisoners, 2 Krupp 1913 pattern field guns and a number of machine-guns. The only fatal casualty was 2nd Lieutenant William Victor Ross Sutton aged 20 buried in Ramleh War Cemetery.

On the 14th November the main objective was Junction Station an important rail junction with the railway running North and South and to the East towards Jerusalem itself. The Yeomanry Division was ordered to continue the advance on Ramleh and Lydda. The Brigade was advancing in an Easterly direction from Qata and El Maghar heading towards Abu Shusheh and Sidon with Junction Station itself being to the south. Units of the 75th Division supported by armoured cars captured Junction Station on the morning of the 14th November breaking the railway link to Jerusalem leaving only the road north to Ramleh with no other route through the mountains except foot or mule tracks. One of the main points of entry to the Judean Hills was the ridge above the village of Abu Shusheh held by a Turkish rearguard. The Divisional Commander was not minded to leave the dominating position of the ridge on the right flank as the move was made towards Ramleh but it was a difficult objective for cavalry being rough faced and studded with great boulders with the village of Abu Shusheh at the northern end and the smaller village of Sidon to the south west.

At 0930 on the 14th November the Regiment moved off as Advanced Guard to the Brigade heading towards Abu Shusheh but after crossing the railway was unable to advance further owing to heavy machine-gun fire. Sergeant Bishop was mortally wounded and 3 other ranks were wounded. The regiment held the right outpost line with the horses being watered at Akir during the night it being described as a very wearing and telling day. At 0945 on the 15th November 1917 the Regiment moved out dismounted to attack Abu Shusheh ridge the attack being completed successfully by 1030. The Berkshire Battery had been ordered into action against the southern part of the ridge with the Berkshire Yeomanry dismounted to move forward against the highest point of the ridge and when that advance was checked the Buckinghamshire Yeomanry was to advance mounted on the right against the lower southern slopes. The horses though slipping kept their feet and the Yeomanry swept onto the ridge; the Berkshire after the Turks on its front had fallen back, mounted and followed but the final attack on the crest had to be made on foot with the Turks thoroughly shaken making no great resistance. 350 were captured and at least the same number killed whilst the Berkshire Battery after the capture of the village of Sidon came up to shell the retreating Turks from the ridge. The total casualties of the Brigade were only 37. The Regiment lost 2 killed, Privates Harry John William Chislett and Francis George Embling (both buried in Jerusalem War Cemetery), and 1 other ranks slightly wounded. The Regiment was relieved at 1600 by the East Riding Yeomanry marching to Ramle to bivouac.

The operations in Palestine formed part of the last great cavalry campaign. Following a period of rest and reorganization the Yeomanry Mounted Division marched into the Judaean Hills when on the 20th November 1917 Lieutenant Richard Frederick Norreys Bertie was killed (buried in Jerusalem War Cemetery). On the following day the Commanding Officer of the Regiment Lieutenant Colonel Arthur Murray Pirie, D.S.O., 21st (Empress of India’s) Lancers attached Berkshire Yeomanry, 2nd Lieutenant Richard Tuckey Hewer, Privates Charles Henry Pain Courtney and Francis William Goldswain were killed all in the same action west of the village of Beitunia. All, with the exception of Private Courtney, are commemorated on the Jerusalem Memorial, but all are buried in Jerusalem War Cemetery. On the 27th November 1917 the Regiment was in camp at Ramle (less one company) when the Camp was attacked by seven Turkish aeroplanes wounding a number of the soldiers and killing a number of horses and mules whilst later the same day an outpost at Abu-Zeitoun held by a dismounted Company of the regiment, 3 officers and 60 men, was bravely defended all afternoon with reinforcements arriving at night but when the order came to withdrawn there remained only 20 soldiers able to fight under Lieutenant L N Sutton. The Turkish attack was finally beaten off and the greatly reduced 6th Mounted Brigade withdrew from the front line for the last time on the 30th November 1917.

In April 1918 the Berkshire Yeomanry was amalgamated with the Buckinghamshire Yeomanry to form the 101st Machine Gun Corps.

The Citation for the D.C.M. in the London Gazette is in the following terms: “For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty. When an advanced guard came under heavy fire from hidden positions he boldly rode forward to locate the guns, and by drawing their fire he was able to disclose their approximate position. He showed magnificent courage and determination.”

Percy Bishop was awarded the Victory Medal and British War Medal and the 1915 Star.

George Smith Busby Corporal No. 307750 1st/8th Battalion Royal Warwickshire Regiment (Territorial Force); died of wounds 24th October 1918 aged 34 and buried in Premont British Cemetery Aisne France, NE of St Quentin. Records 521 UK, 7 Aust., 6 Can., 1SA., 1 Ind., and 36 German burials.

George Busby was the son of William and Mary Ann Busby of Brockhurst Monks Kirby; he enlisted at Coventry. In 1901 William Busby aged 42, an Agricultural Labourer, lived at 1 Main Street Monks Kirby with his wife Mary Ann aged 44 and sons George Smith Busby aged 16 a Gardener and William aged 14 also a Gardener.

A Notice in the Rugby Advertiser dated 16th November 1918 refers to George as their second son and that William and Mary had two other sons fighting, one in Egypt and one in France, suggesting that George had an older brother.

The 1st/8th a Territorial Battalion formed at Aston Manor Birmingham on the 4th August 1914 and as part of 143rd Brigade entrained for Southampton crossing the Channel and landing at Le Havre on the 22nd March 1915.

The Brigade remained on the Western Front fighting in the Trench warfare in Northern France and in the Battle of the Somme and the Third Battle of Ypres until, as part of 48th Division the Brigade went to Italy at the end of November 1917 remaining there until the 14th September 1918. The Battalion entrained for France on the 14th September 1918 and arrived at Yvrencheux about 9 miles North East of Abbeville on the 19th September 1918.

On the 21st March 1918 the German Army launched a massive offensive on the Western Front in a last desperate attempt to score a decisive victory. The results were spectacular. They advanced up to 40 miles, further by far than the British and French had managed in their offensives on the Somme, the Aisne and at Ypres. The British Fifth Army was crushed, and the Allies suffered 212,000 casualties. The French suffered a humiliating defeat at Chemin des Dames and plans were made for the evacuation of Paris. The British were seriously concerned that the French might sue for peace and were uncertain whether they could continue the struggle, and plans were drawn up for the evacuation of the British Army from France if Dunkirk, Calais or Boulogne fell. The German line before the offensive was about 20 miles East of Noyon, on the western edge of St Quentin, 15 miles East of Peronne, 20miles East of Bapaume, 7 miles East of Arras, 5 miles East of Armentieres, 25 miles East of Bailleul and 12 miles East of Ypres. Then the offensive gradually lost momentum, the French counterattacked in July, the British in August and the Germans finally lost the initiative. After the offensive the German Army had reached positions some 15 miles West of Noyon, 45 miles West of St. Quentin, 20 miles West of Peronne, 12 miles West of Bapaume, still 7 miles East of Arras, 28 miles West of Armentieres, 8 miles West of Bailleul and 4 miles East of Ypres.

The Counter-Attack in Champagne by mainly the French Army was from 20th July to 2nd August 1918.

On the 8th August 1918 the Allied forces launched the surprise attack that heralded the end of the First World War. With skill and daring 21 Divisions breached the German lines, supported by 500 tanks (the largest number to have been seen in any one battle of the war) and 1000 aircraft. In their wake they left 50,000 dead or wounded German soldiers along a stretch of 11 miles. On this “black day” for the Germans the Allied forces began to see a glimmer of hope and the dawn of victory that was to come only 100 days later with the Armistice on 11 November 1918. The Advance to Victory can be divided into 7 phases, The Advance in Picardy 8th August-3rd September, The Advance in Flanders 18th August-6th September, The Breaking of the Hindenburg Line 26th August-12th October,The Pursuit to the Selle 9th-12th October,The Final Advance – Flanders 28th September-11thNovember, The Final Advance – Artois 2nd October-11th November and The Final Advance – Picardy 17th October – 11th November 1918.

On the 1st October 1918 the Battalion was at Combles on the Somme and came into the line on the 5th October. By that date the Front Line in Fourth Army sector (25th Division being in Fourth Army) was some 5 miles East of the St Quentin Canal and the main Hindenburg defensive system built between the northern and central sectors of the Western Front by the Germans from September 1916 and to which in the and was then assigned to the 75th Brigade in the 25th Division. Spring of 1917 the Germans in the central sector withdrew. The Canal had been crossed at the end of September 1918 and the Fourth Army had advanced some 6000 yards towards the Beaurevoir Line, the last German position on this section of the front. The Battalion was in support in the capture of Guisancourt and Helle Ville Farms, strongpoints on the Beaurevoir Line, on the 6th and 7th October and then in support to the 1/8th Worcestershire Regiment who had captured the village of Beaurevoir. On the 8th October the village of Premont fell to the American Army and Serrain to the 25th Division. The advance continued on the 9th October with Maretz being captured with troops reaching the outskirts of Honnechy and Maurois. Starting from a point North of Honnechy at 0530 on the 10th October the Battalion advanced after heavy fighting to the outskirts of Le Cateau the advance failing to reach the high ground east of Le Cateau and the Division was held up along the River Selle and in the western outskirts of the town. From the 12th to the 16th October the division remained in the Serain – Premont – Ellincourt area in corps reserve for a short rest after the strenuous work of the previous days. At 0520 on the 17th October the 18th and 50th Divisions attacked along the line of the River Selle south of Le Cateau to cross the river between St Benin and Le Cateau early on the morning of the 18th October which was greatly hindered by thick mist and severe shelling west of the railway where most of the bridges had been destroyed. The 75th Brigade had been attached to the 50th Division and the Battalion was in support to the 1/8th Worcesters and 1/5th Gloucesters reaching their objective the line of the Bazuel – Le Cateau road and then the village of Bazuel captured on the 19th October some 3 miles south east of Le Cateau. On the 20th October the Battalion marched out to St Benn resting there until the evening of the 22nd October.

At a Conference on the 19th October General Sir Henry Rawlinson, Commander of the Fourth Army, had outlined the next phase of the Battle of the Selle, the Army being reduced to two Corps the American II Corps being drawn into G.H.Q. Reserve, its role being to form a defensive flank facing East to protect the main operation of the Third and First Armies. The 25th Division as part of XIII Corps was to secure the Landrecies – Englefontaine road, some 5 miles distant, on the western side of the Forest of Mormal, taking the village of Pommereuil, the northern part of l’Eveque Wood, Fontaine au Bois, Bousies and Robertsart. An essential object was to obtain artillery positions from which the railway junction of Aulnoye (8 miles east of Englefontaine, on the eastern side of the Forest of Mormal) could be kept under 6 inch British gun fire.

Zero hour was at 0120 on the 23rd October 1918 with the ground being soft and sticky from rain and though the moon was bright a ground mist prevailed until 0900 limiting visibility to 50 to 60 yards the Battalion forming up along the railway line just behind the Infantry Starting Line with the first objective, the village of Pommereuil some 3000 yards away.

The Battalion had been attached to the 7th Brigade for this operation and had been employed in clearing up small parties of Germans and in particular Machine Gun posts overrun in the dark by the attacking battalions of the 7th Brigade, 20th and 21st Manchesters and 9th Devons. By 0600 the battalions were established along the line of their first objective, the village of Pommereuil had been captured and the battalions had begun the arduous task of clearing the northern half of l’Eveque Wood but in spite of hostile resistance and the thick undergrowth this had been successfully accomplished by 0730 and by 2000 that evening the British had advanced beyond Bousies the 4th objective.

On the 24th October the 74th Brigade continued the attack through the Bois l’Eveque, with the Battalion being ordered to concentrate in the vicinity of Flaquet Brifaut which they completed by 1053 remaining until units of the 7th Brigade passed through when the Battalion marched out to billets in Pommeruil.

During this tour of duty the Battalion had 13 Other Ranks killed, 5 missing and 40 Wounded with 3 officers being wounded as well. Corporal Busby was almost certainly wounded on the 23rd October when he received a gunshot wound in his side. On the 23rd October Private Charles Eversden commemorated on the Memorial at Withybrook was killed. Corporal Busby was taken back to the area North East of St Quentin where the 75th, 76th and 77th Field Ambulances were established but he succumbed to his wound, dying on the 24th October 1918.

George Busby was awarded the Victory Medal and the British War Medal.

The Honourable Hugh Cecil Robert Feilding, Lieutenant Commander Royal Navy. Killed in action on 31st May 1916 aged 29 on HMS Defence at the Battle of Jutland. Hugh Feilding is commemorated on the Plymouth Memorial on the north side of The Hoe Plymouth which lists over 7000 lost at sea in the Great War.

The Hon. Hugh Feilding was the second eldest son of the 9th Earl of Denbigh and Countess of Denbigh (nee the Hon. Cecilia Clifford of Chudleigh, Devon) of Newnham Paddox, Monks Kirby, Rugby, born on the 30th December 1886. He was educated at the Oratory School Edgbaston Birmingham.

His elder brother Viscount Rudolph Feilding, born on the 12th October 1885, served with the Coldstream Guards transferring to the Battalion from the Special Reserve on the 5th August 1914, was on the Staff from 21st July 1915 to 24th February 1917, then A.A. & Q.M.G. 8th Division from 25th February 1917 to 14th November 1918 and then A.A.G. until the 14th April 1919 as Brevet Lieutenant Colonel. His youngest brother the Honourable Henry Feilding, born on the 29th June 1894, died of wounds on the 9th October 1917.

The Honourable Hugh Feilding had seven sisters, Lady Mary Alice Clara Feilding born 31st March 1888, Lady Dorothie Mary Evelyn Feilding born 6th October 1889 (who served as an Ambulance Driver in the Great War and was awarded the 1914 Star and the Military Medal), Lady Agnes May Mabel Feilding born 13th September 1891, Lady Marjorie Winifrede Feilding born 4th September 1892, Lady Clare Mary Cecilia Feilding born 23rd November 1896, Lady Elizabeth Mary Feilding born 22nd August 1899 and Lady Victoria Mary Dolores Feilding born 29th March 1901.

Other relatives included Geoffrey P. T. Feilding who commanded the 3rd Battalion Coldstream Guards in 1914 subsequently being promoted to command the 4th and 1st Guards Brigades and then the Guards Division from January 1916 until September 1918 and then until January 1920 Major General G.O.C. H.Q.L.D. and Rowland Feilding who transferred to the Coldstream Guards from the London Yeomanry on the 6th April 1915, commanded the 6th Connaught Rangers from 6th September 1916 to 18th August 1918, then the 1st Civil Service Rifles until his demobilization on the 13th December 1919.

At outbreak of the War the Honourable Hugh Feilding was Torpedo Lieutenant in Defence which was then the Flagship of the Mediterranean Cruiser Squadron. He had been torpedo officer of the Defence for 3 ½ years and for the last few months 1st Lieutenant. On leaving the Oratory School Edgbaston he went to the cadet training ship HMS Brittania where he passed as Midshipman and obtained the prize for highest aggregate marks. He served as Midshipman on the Mediterranean Station in HMS Bacchante and the South African Station in HMS Crescent. He gained the coveted “six ones” in his examination for Lieutenant as well as the special promotion marks for “meritorious examination” which caused him later on to be antedated in his career considerably, his rank as Lieutenant dated within a few days of his 20th birthday. He was awarded the Beaufort testimonial and the Wharton testimonial with gold medal for highest marks in navigation and pilotage and also the Ronald Megaw prize and sword given to the one obtaining the highest marks in the examination for Lieutenant. He specialized for torpedo after serving at sea in HMS Queen and also in HMS Cornwall. He passed very high in the advanced course at Greenwich after which he served in HMS Vernon and was then appointed to the Defence

In 1897 the British Empire comprised one quarter of the land surface of the globe and one quarter of the world’s population. The Empire was guarded by the fleet of the Royal Navy. As well more than half the steamships travelling the oceans in 1897 flew the Red Ensign of the British merchant navy.

When Kaiser Wilhelm II became Emperor of Germany in 1888 he became jealous of Great Britain’s imperial position, her empire and her fleet and sought to acquire a navy equal to that of Great Britain when in the 1890s the German navy was little more than a costal defence force. The Reichstag (the German Parliament) felt it sufficient to maintain the largest and most powerful army in Europe and was adverse to a huge naval expenditure but when the Kaiser appointed Alfred von Tirpitz as Secretary of the Imperial Navy Office in 1897 he was eventually able to convince the Reichstag on the basis of the need to defend Germany rather than the expansionist ideas of Kaiser Wilhelm of the need to build warships and on the 10th April 1898 the Reichstag passed the first Naval Bill which called for the construction of 19 battleships, 8 armoured cruisers and 12 large and 30 light cruisers all to be completed by April 1904.

This proposal would mean a fleet significantly less strong than the British Fleet which was at that time double the strength of the French and Russian Fleets combined, based on the principle that Britain would build ships of war to a two-power standard, that is to match at least the combined forces of whichever two countries possessed the largest navies after its own.

Then in February 1906 HMS Dreadnought was launched undergoing sea trials in October of that year and the novel features, turbine engines, ten 12 inch guns some sited to fire forward, coupled with improvements in naval gunnery (smokeless power and range-finders) made obsolete all existing battleships, including the British fleet.

This was followed in April 1907 with the launch of the Invincible, a new type of armoured cruiser (later reclassified as a battlecruiser) mounting eight 12 inch guns and also turbine powered, capable of a top speed of 25 knots and being so fast and powerful, the Invincible likewise rendered obsolete all existing types. There was only one flaw: the characteristics of a warship are guns, speed and armour. If heavy guns and heavy armour were required then speed had to be curtailed and this compromise was built into battleships but if higher speed was demanded, armour had to be sacrificed and this was the position with the Invincible. Dreadnoughts were fitted with armour plate eleven inches thick, enough to stop a plunging shell but in the Invincible class, the armour over the vital midships spaces was only seven inches thick.

This disturbing news (to the Germans) resulted in a further approach to the Reichstag for funds to build a German equivalent to the Dreadnought (and also broaden and deepen the Kiel canal which allowed the Germans to transfer their fleet between the North Sea and the Baltic). The first class of German dreadnoughts – the four Nassaus – were laid down in the summer of 1907 but were provided with better and more extensive armour protection by a slight reduction in the guns, for example twelve 11 inch guns, or ten 12 inch guns.

In August 1914 Britain could deploy twenty Dreadnoughts (with twelve more in the course of construction) to the Germans’ thirteen (with seven building), and nine battle cruisers (with one building) to the Germans’ five (with three building). In addition the royal Navy enjoyed a twofold advantage in pre-Dreadnought battleships and a threefold lead in cruisers. However Britain had only 42 Destroyers compared to Germany’s 88 but Britain had 55 submarines, almost twice as many as Germany with only 28.

Before the outbreak of the War, the Royal Navy had adopted an operational plan which envisaged a distant blockade of Germany coupled with stationing the Grand Fleet in a position where it could stand on the alert ready to pounce on part or all of the German navy whenever it put to sea.

The British Isles lay like a breakwater across the sea approaches to Germany with two gaps, in the south the English Channel 20 miles across easily guarded by a small naval force of pre-dreadnought battleships, destroyers and cruisers coupled with a mine field which reduced the gap substantially and in the north the gap from the Orkneys to Norway guarded by the Grant Fleet at its base in Scapa Flow with patrolling cruisers out in the North Sea itself.

The Grand Fleet had been gathered together for the review by George V at Spithead on the 17th July 1914 and the ordinary dispersal of the fleet was cancelled and the Fleet was moved to its war stations at Scapa Flow.

Prior to the Battle of Jutland, there had been three clashes between British and German naval forces in 1914 and one in 1915. On the 28th August 1914 British and German cruisers had clashed at Heligoland Bight, on the 2nd November there was a tip and run raid by German battle cruisers on the East Coast with Yarmouth being bombarded and then on the 15th December German forces crossed the North Sea to bombard Scarborough, Hartlepool and Whitby but the Admiralty had found out about this raid by decoding German naval messages. On the 26th August 1914 the German light cruiser Magdeburg had run aground in the Gulf of Finland and had been destroyed by two Russian cruisers. Copies of the German Navy’s cipher signal books and charts had been recovered from a drowned signalman and these were sent to the British Admiralty who had picked up messages from British listening stations. To intercept the German raiders, the plan was for Battlecruisers, cruisers and the 2nd Battle Squadron to rendezvous off the south east corner of Dogger Bank but in fact the force was so placed to be on a collision course with the German High Seas Fleet. In December 1914 Admiral Sir David Beatty’s battlecruiser force was moved from Scapa Flow to Rosyth to make interception of German raids on East Coast towns of Great Britain easier. Warned of a new German raid on the night of 23 – 24th January 1915 by radio intercepts, Beatty’s force made for a rendezvous off the Dogger Bank again, supported by light cruisers from Harwich, armoured cruisers and a squadron of battleships from Rosyth with the Grand Fleet commanded by Sir John Jellicoe moving south. The light cruisers sighted German units at 7.15 a.m. and the outnumbered Germans turned in flight and in the running fight which followed the faster British battlecruisers failed to overhaul and destroy the German force largely through a series of misunderstood orders although Hipper’s flagship SMS Seydlitz and Beatty’s flagship HMS Lion were both badly damaged and the armoured German cruiser Blucher was sunk.

In January 1916 Admiral Reinhard Scheer became the new commander of the German High Seas Fleet and sought to produce a plan not dissimilar to those of 1914/1915 to lure elements of the British fleet to their doom until the British fleet was outnumbered by the German fleet and this was the basis of the scheme which led to the Battle of Jutland.

At 2.00 a.m. in the morning of the 31st May Vizeadmiral Franz von Hipper’s battlecruiser force, which had spent the night at anchor in the outer estuary of the Jade River proceeded to sea passing to the west of Heligoland and advancing north towards the Skagerrak. His force consisted of 5 battlecruisers, 4 light cruisers and 30 destroyers led by another light cruiser and this force was to proceed to Scandinavian waters as if to interfere with the British blockade whilst the main German Battle Fleet led by Admiral Scheer would follow more secretively some distance back. It was expected that this would bring the Grand Fleet out of its bases in Scotland to be attacked by U-boats who would report British movements and Beatty’s battle cruisers would rush across the North Sea expecting only to meet again Hipper’s battlecruisers but would fall instead under the guns of the German High Seas fleet.

At 3.30 a.m. Admiral Scheer ordered the German High Seas fleet to sea and he had 16 dreadnought type battleships, 5 light cruisers and 31 destroyers with 6 pre-dreadnought battleships which joined the rear of his force at about 5.00 a.m. south west of Heligoland.

However by the morning of the 30th May the British were aware that the High Seas Fleet was assembling in the outer anchorages of the Jade and Sir John Jellicoe was at 12 noon warned that the German Fleet would probably put to sea early on the morning of the 31st May; later in the afternoon through decoding of radio messages a major operation was suspected and at 5.40 p.m. Jellicoe received the order to take his fleet to sea and by late evening his 16 Dreadnoughts had left Scapa Flow. A similar order had been issued to Sir David Beatty who left Rosyth with 6 battle cruisers and the 4 super dreadnoughts of the 5th Battle Squadron. The super dreadnoughts were oil fired and armed with eight 15 inch guns. The concentration was to be east of the Long Forties about 100 miles east of Aberdeen.

By 11.30 p.m. on the 30th May, more than 2 hours before the battlecruisers of Hipper had even left the Jade, all formations of the Grand Fleet were at sea. From Scapa under Jellicoe were the 1st and 4th Battle Squadrons, the 3rd Battlecruiser Squadron, the 2nd Cruiser Squadron, the 4th Light Cruiser Squadron and the 4th and 12th Destroyer Flotillas with one division from the 11th Flotilla. From Cromarty under Vice Admiral Jerram were the 2nd Battle Squadron, the 1st Cruiser Squadron and 10 destroyers of the 11th Flotilla. From Rosyth under Vice-Admiral Beatty were the 1st and 2nd Batlecruiser Squadrons, the 5th Battle Squadron and the 1st, 2nd 3rd Light Cruiser Squadrons plus 27 destroyers. A total of 151 Royal Navy warships – 28 dreadnought battleships, 9 battlecruisers, 8 armoured cruisers 26 light cruisers, 78 destroyers, a minelayer and a seaplane carrier had put to sea.

HMS Defence was the flagship of Rear Admiral Sir Robert Arbuthnot and with HMS Warrior, HMS Duke of Edinburgh and HMS Black Prince formed the 1st Cruiser Squadron which had sailed from Cromarty.

HMS Defence was a Minotaur-class armoured cruiser built at Pembroke dockyard and launched on the 24th April 1907 and was the last armoured cruiser built for the Royal Navy. She displaced 14,600 tons and had a speed of 22.9 knots. She was armed with 4 x 9.2 inch guns, 10 x 7.5 inch guns and 16 quick firing 12 pounder 18 cwt guns with 5 submerged 18 inch torpedo tubes. Speed being a requirement, armour was sacrificed and the belt was only six inches thick, not enough to stop a heavy plunging shell. Her complement was 54 officers and 849 enlisted men.

HMS Defence served with the 1st Cruiser Squadron from July 1909 and then in early 1913 was on the China station before rejoining the 1st Cruiser Squadron.

In early 1914 she was stationed in the Mediterranean, was involved in the pursuit of the Goeben and Breslau and then spent September outside the Dardenelles. She was ordered to the South Atlantic to take part in the hunt for Admiral Graf von Spees’ squadron but that squadron was destroyed on the 8th December before she could reach the area and the ship was then diverted to the Cape of Good Hope rejoining the 1st Cruiser Squadron in January 1915.

Jellicoe intended to reach the rendezvous at about 2.30 p.m. on the 31st May but expected Beatty’s force to be some 70 miles to the south, his prime task with his speedier vessels being to locate the enemy which was still expected to be only Hipper’s Battle Cruisers. If Beatty had not located the enemy he was to turn north to the meet the Grand Fleet.

The German U-boat trap failed but two U-boats were able to sight units of the British fleet and about 8.00 a.m. had sent two wireless messages but this did not enable Scheer to deduce even the fact that the whole of the Grand Fleet had put to sea. By that time Hipper’s Battle Cruisers had gained the open sea, Scheer’s battlefleet would not reach that point until 10.00 a.m.

Just before 2.30 p.m. Beatty had proceeded due East to about the point where he was to turn North with still no trace the German fleet which equally unaware of Beatty’s force was heading North towards Beatty with Jutland to its East and the Skagerrak to its North East, the High Seas rendezvous being in the mouth of the Skagerrak. The most easterly ship of Beatty’s screen, the light cruiser HMS Galatea sighted a Danish tramp steamer and went to investigate and this ship had also been spotted by the German light cruiser Elbing which sent two German destroyers to investigate. The German ships spotted the smoke from the approaching HMS Galatea which had also spotted the German ships, mistaking them for light cruisers sent a wireless message to the British fleet 2 cruisers probably hostile in sight. Both the Galatea and the Elbing opened fire at about 2.20 p.m. whilst both Jellicoe aboard the Iron Duke and Beatty aboard the Lion altered course appropriately, albeit Jellico still believing the German High Seas Fleet was still not at sea. Galatea then spotted and reported dense clouds of smoke from the north east indicating a large hostile fleet and Beatty then knew the position of Hipper’s battle cruisers and moved to engage them.

At about 3.20 p.m. Hipper’s force sighted Beatty’s and turned south hoping to draw the British Battle Cruisers onto the guns of Scheer’s High Seas battleships with a long range gunnery duel developing in which at about 5.00 pm the battlecruiser HMS Indefatigable was sunk and at about 5.25 p.m. the battlecruiser HMS Queen Mary was sunk , 57 officers and 960 men going down with Indefatigable and 57 officers and 1,209 men with the Queen Mary. Shortly before HMS Queen Mary had been sunk by the combined fire of two German battlecruisers, the 5th Battle Squadron consisting of four of the most powerful battleships in the British fleet had caught up and by 5.00 p.m. began fire on the German ships at the rear of Hipper’s force. About half an hour later the light cruiser Southampton some two miles ahead of the Lion spotted a light cruiser to the south-east, the Rostock ahead of the German battlefleet and then from the Southampton was sighted the topmasts of a long line of battleships surrounded by destroyers and at 5.38 p.m. a wireless signal was sent to Beatty and Jellicoe that the enemy battle fleet had been sighted, the signal coming as a surprise to Beatty as he was still under the impression that the German battle fleet had not left the Jade anchorage and the message which actually reached the Iron Duke had become garbled leading Jellicoe to believe that he was facing a German force of 18 German dreadnoughts and 10 pre-dreadnoughts rather than the actual 16 German dreadnoughts and 6 pre-dreadnoughts.

Now that the German battleships of Admiral Scheers fleet had been spotted, Beatty’s task changed and his priority was now to bring Scheers battleships into contact with the superior force of Admiral Jellicoe which required his force to turn north, Evan-Thomas’ 5th Battle Squadron bringing up the rear becoming engaged with the leading battleships of Scheers fleet, the British force being re-inforced by the 3rd Battle Cruiser Sqadron which had been stationed at Scapa Flow and had been sent ahead by Jellicoe to assist Beatty which forced Hippers German battle cruisers back towards Admiral Scheer making them unable to warn Scheer of the great danger forming up over the horizon, the Grand Fleet.

At about 7.00 p.m. the port wing battleships of the Grand Fleet had been sighted about 4 miles north of the Lion and to prevent Hipper from sighting and reporting the intervention of the British battlefleet, Beatty altered course to the east and the range between his ships and Hipper’s decreased subjecting those enemy ships to overwhelming fire without being able to reply. Derflinger was hit by a heavy shell and began to sink by the head and the Seydlitz was also hit, and Hipper turned his force to the south west and as that turn was being effected Admiral Hood’s 3rd Battlecruiser Squadron passed some 18 miles to the East of Beatty’s force to reach a position some 25 miles south-east of the Grand Fleet without sighting either Beatty’s force or the German forces. Ahead of Hood’s force were scouting cruisers one of which was HMS Chester which turned towards the outlines of ships believing these to be Beatty’s van when in fact it was a German scouting group stationed some 5 miles north-east of German battlecruisers and she was exposed to gun fire from four German ships including the Wiesbaden. HMS Chester, damaged and with numerous casualties, turned to the north towards Hood’s squadron which observing the flash of gunfire altered course moving to support the Chester and caught a group of German light cruisers cold with little to fear from their relatively diminutive opponents. Two of the German ships were badly hit, especially the Wiesbaden which was left with both engines disabled and stationary.

At that stage whilst two of the British battlecruisers had been sunk by internal explosions, Hipper’s flagship Lutzow was listing heavily and was out of the line, Derflinger had water streaming in through a hole in the bows, Seydlitz was awash up to the middle deck and listing to port, Von de Tann had no gun turrets in action and only the Moltke remained serviceable and to this ship Hipper transferred his flag.

The two main fleets were now rapidly closing, Jellicoe’s fleet being deployed in six columns over a width of some 4 miles.

At about 6.30 p.m. the Grand Fleet was sailing in five columns heading south east with a screen, 4th Light Cruiser Squadron, ahead and then in front of those ships HMS Duke of Edinburgh, HMS Warrior and HMS Defence. HMS Chester had turned north and was about 10 Nautical Miles ahead to the south east. By 7.00 p.m. HMS Lion had got to a position in front of Jellicoe’s Grand Fleet, HMS Chester was about 4 nautical miles to the East and about the same distance ahead of Warrior and Defence was the German light cruiser Wiesbaden disabled with no engine power. The British 3rd and 4th Light Cruiser Squadrons advanced from behind Defence and Warrior to deliver a torpedo attack on the leading ships of Hipper’s fleet, and one the Falmouth discharged a torpedo at Wiesbaden. Shortly after 7.00 p.m. the armoured cruisers Defence and Warrior made their way towards the Wiesbaden, crossing the course of the British battlecruisers, so close to the bow of the Lion that the battlecruisers were forced to turn hard to port t avoid the two cruisers. It remains difficult to understand why Jellicoe had kept these old cruisers some three miles in advance of his battleships, as presumably some form of screen. Their slowness made them useless as scouts; their armament left them an easy prey to German battle-cruisers. If Rear Admiral Arbuthnot flying his flag in Defence believed that the destruction of the Weisbaden was to be an easy matter he was quickly disillusioned. Both Warrior and Defence began to fire their 9 inch guns at Wiesbaden perhaps because he feared she might use her torpedoes against the British Grand Fleet or more likely because he had expressed the intention that if his Squadron encountered the enemy he would close to the range of his guns and engage the German ships. As the British cruisers opened fire, looming up from the south west of the Defence appeared the huge outlines of the German battlecruisers and the German battleships of III Squadron. A ship with four funnels was sighted from the Lutzow at first thought to be the German light cruiser Rostock but it was quickly realised that astonishingly it was the old armoured cruiser Defence and the Lutzow and Derfflinger opened fire as did four advancing German Battleships. Salvo after salvo fell, in a moment the Defence was enveloped in columns of water from exploding shells, then the Defence was struck aft and forward so immense flames gushed from the gun turrets and then an explosion followed, heard by ships from both fleets, followed with a huge sheet of flame 1,000 feet high and smoke gushing forth and at about 7.20 p.m. the Defence sank, wreckage continuing to fall into the water for some time after the explosion.

54 officers including Admiral Sir Robert Arbuthnot and Lieutenant Commander the Honourable Hugh Feilding and 849 men were killed.

An officer serving on HMS Obedient of 12th Destroyer Flotilla saw the 1st Cruiser Squadron led by Defence emerge out of the mist the ship being heavily engaged with salvoes dropping all around her. The three salvoes reached the Defence, the first went over the second fell short whilst the third hit near the after turret when a flash of flame appeared and as quickly vanished. Defence heeled over but quickly righted herself and steamed on and then almost at once came three more salvoes the third hitting Defence between the forecastle turret and the foremost funnel. At once the ship was lost to sight in an enormous cloud of black smoke with perhaps a funnel twirling into space. When the smoke cleared Defence had gone.

Commander George van Hase was Chief Gunnery Officer on the German Battlecruiser Derflinger. A colleague spotted a cruiser with four funnels and asked if it was English or German. He examined the ship through his periscope and concluded it was English. His gunnery officer asked if he should open fire and was told to fire away. Just as Lieutenant Commander Hausser was about to order “Fire” the English ship broke up and there was an enormous explosion, black smoke and pieces whirled upwards and flame swept the entire ship which disappeared beneath the waves before their eyes. There was nothing left but an enormous cloud of smoke. Commander van Hase believed it was the fire of Lutzow just ahead of Derflinger which had destroyed HMS Defence.

Warrior following behind Defence was also hit near the bow and set on fire but shrouded in her own smoke was able to make her way to the west and temporary safety but the following day whilst under tow back to England was abandoned and sank.

At about 7.30 p.m. the 3rd Battlecruiser Squadron steering a course parallel to Hipper’s squadron was subjecting the Lutzow and Derflinger to a storm of heavy shells when Invincible was struck by a salvo probably from the Lutzow which pierced the ship’s armour and detonated inside the ship, the explosion tearing the ship in two 1,020 officers and men perishing in the explosion.

It was about this time that an uninterrupted line of gun flashes showed up along the entire horizon ahead of the German Fleet so that Admiral Scheer appreciated for the first time that he had placed the German High Seas Fleet in the same stretch of water as the British Grand Fleet with his 22 German battleships strung out in a line nine miles long while the 24 battleships of the Grand Fleet had deployed in a line some 5 miles long and already firing on Hipper’s battle cruisers.

Admiral Scheer had to break off contact with the British and return to the safety of a German harbour and to achieve the first he ordered each of his vessels to turn 180 degrees so his last battleship became the first in the line and the former first the last, heading south west and away from the German coast. That contact had broken was not at once obvious to Jellicoe, observations hampered by mist, funnel and enemy smoke screens but when it was appreciated Jellicoe set the Grand Fleet on a southerly course to place the fleet between the High Seas Fleet and its base. Later Admiral Scheer ordered another 180 degree turn and with the battlecruisers again in the vanguard headed for port but again his ships collided with the Grand Fleet, which brought down a heavy fire on the German ships until a German destroyer flotilla launched a torpedo strike which was unsuccessful but led to Admiral Jellico ordering a change of course for the Grand Fleet to the south east, that is away from the High Seas fleet and with nightfall at about 9.00 p.m. Admiral Scheer was able to escape eastward across the rear of the Grand Fleet in the darkness to reach the safety of Wilhelmshaven.

The consequences were that the Royal Navy suffered the more serious losses – three battlecruisers, three armoured cruisers and eight destroyers (111,000 tons) to Germany’s one battleship, five cruisers and five destroyers (62,000 tons) and 6,097 sailors to Germany’s 2,545 but the Grand Fleet despite its losses was ready to put to sea almost immediately whilst the High Seas Fleet would require several weeks before it was in a fit state to leave harbour. Of more importance the balance of naval power was not remotely affected. On the 1st June the Grand Fleet was scouring the North Sea seeking its enemy whilst the German fleet was once more at rest in harbour: British and German capital ships would not again exchange fire during the Great War.

After the Battle of Jutland in which the Germans inflicted heavier losses but the British retained command of the North Sea, both sides used naval means to cut the other’s supply lines in a war of attrition. The British instituted an open blockade of the Central Powers which became effective by the end of 1916. In that year there were 56 food riots in German cities. In reply the Germans resorted to unrestricted submarine warfare in February 1917 and one out of every four ships leaving British ports was sunk. The assault was only checked by the convoy system first used in May 1917.

Allied shipping losses in the period 1914 – 1918, all in tons, for Britain were 7,800,000 , France 900,000 , Italy 872,000 , United States while neutral 56,000 and while belligerent 397,000, Greece 346,000 and Russia 183,000.

The wreck of the Defence was discovered by a diving team in 2001 and was found to be largely intact, cordite had been hit and this had caused immense smoke and heat, sufficient to melt the hull. The wreck lies in around 45 metres of water upright and on an even keel.

The Honourable Henry Simon Feilding, Lieutenant (Acting Captain) 2nd Battalion Coldstream Guards died of wounds 11th October 1917 October aged 23. Buried Dozinghem Military Cemetery, Westvleteren, West Flanders. This cemetery was one of three created at the outset of 3rd Ypres, the others being Mendinghem British Cemetery, Proven, West Flanders and Haringhe (Bandaghem) Military Cemetery, Rousbrugge-Haringhe, West Flanders. Dozinghem Cemetery records 3,021 UK., 61 Can., 34 B.W.I., 19 Newfld., 15 S.A., 14 N.Z., 6 Aust., 1 Unknown 3 Chinese and 65 German burials.

Third and youngest son of Rudolph Robert Feilding 9th Earl of Denbigh and Desmond (1859 – 1939) and Countess Denbigh of Newnham Paddox, Monks Kirby, Rugby. The Earl served in Egypt from April 1915 to January 1916 with the 2nd Mounted Division, subsequently Artillery Staff Southern Army Eastern Command in 1916.

His brothers were Rudolph Edmund Viscount Feilding (1885 – 1937), eldest son of the 9th Earl who joined the Army in 1906 and was appointed Lieutenant in 1909 went to France in 1914 and on the 19th December 1914 was a Captain commanding No. 1 Company 3rd Coldstream Guards, and the Honourable Hugh Feilding (1886 – 1916) a professional Naval Officer killed at the Battle of Jutland on the 31st May 1915.

He had seven sisters born between 1888 and 1901 detailed in the entry for his brother the Honourable Hugh Feilding.

Henry Feilding was born on the 29th June 1894 and was educated at the Oratory School Edgbaston and Trinity College Cambridge and held a commission as 2nd Lieutenant with King Edward’s Horse (The King’s Overseas Dominions Regiment)(formed in 1901) part of the Special Reserve joining the regiment on the 7th August 1914 on mobilisation.

On the 25th April 1915 Henry Feilding as part of C Squadron of King Edwards Horse arrived in France from England, the Squadron to become the 47th (London) Division’s divisional cavalry. On the 23rd September 1915 he was appointed Aide-de-Camp to Major General Henry Horne General Officer Commanding 2nd Division since January 1st 1915 and went with him to Egypt in January 1916 when General Horne was promoted Lieutenant General commanding the Northern Section of the Suez Canal defences. General Horne was recalled to France in April 1916 to command XV Corps then in the course of formation as part of the Fourth Army. Lieutenant Feilding resigned this post of ADC by June 1916 and transferred to the Coldstream Guards on the 11th June 1916 and joined the depot at Windsor.

On the 13th August 1914 the 3rd Battalion Coldstream Guards landed at Havre the CO being Lieutenant Colonel Geoffrey Feilding D.S.O. (cousin of the 9th Earl) subsequently Major General Sir Geoffrey Feilding.

On the 6th April 1915 Captain Rowland Feilding joined the Coldstream Guards from the 2nd Battalion City of London Yeomanry having lobbied his cousin Geoffrey Feilding. He landed at Harfleur on the 29th April 1915 and on the 3rd May joined the 3rd Battalion Coldstream Guards. He subsequently transferred to the 1st Battalion and then in September 1916 was transferred to command the 6th Battalion the Connaught Rangers with the rank of Lieutenant Colonel until April 1918; in August 1918 he was appointed to command the 1/15th (County of London) Battalion of the London Regiment (Prince of Wales’s Own Civil Service Rifles). He wrote regularly to his wife Edith and his eldest daughter Joan and in 1929 a collection of these letters were published under the title “War Letters to a Wife.”

By the 3rd May Rowland Feilding had reached the village of Le Preol then about 2 miles East of Bethune (now swallowed up in the suburbs of that town) some 3 miles West of the front line. The 3rd Battalion was billeted there and on the evening of the 4th May Captain Rowland Feilding went into the trenches in the Givenchy sector where the line the Coldstream Guards were holding ran through the village of Givenchy itself of which practically nothing remained. It was in that sector that on the 6th May 1915 Captain Rudolph Feilding brought his younger brother Henry to see his 2nd cousin Rowland. The following day, 5th May 1915, Rowland Feilding’s company was moved south of the La Bassee canal, to the Cuinchy sub sector, named after a small village just behind the British lines unique due to the presence of about 30 brickstacks about 16 feet high and about 12 square yards in area some held by the Germans and some by the British.